Threads, Mastodon, and the Loneliness of Social Media

Why the debate about social media is not about tech or the internet at all.

Were you popular in high school?

It’s probably been a long time since you’ve last thought about your teenage years, but try to imagine them anyway. When you were 15 or 16 years old, how did you feel walking into a classroom or the school cafeteria? How much anxiety, if any, did you feel while looking around for your friends?

If you were anything like me, you might already feel your palms sweating. Simply recalling those years fills me with dread, my blood freezing with utter terror. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to fully get past the scars that being one of the “losers” at school has left me with. And I wouldn’t be surprised if many of you reading these words might have your own scars, healed but never forgotten.

When I opened Threads for the first time, my brain reverted to that of a panicked and insecure teenager. Meta’s new social media app made me feel like I was a loser nerd, walking into a new school’s cafeteria. And as always, the popular kids could smell that I didn’t belong.

If you’re brave enough, follow me down memory lane, and I hope you’ll understand why the current fight over the next great social media platform has very little to do with tech or the internet itself. Instead, we need to analyze Threads, Mastodon, Bluesky, or any other platform by focusing on the very first word of their name: social media. Because like it or not, all social media platforms are about people. And people can be pretty freaking complicated.

The High School Cafeteria and Influencer Hierarchies

If your own high school didn’t have a ridiculously rigid social caste system, allow me to paint a picture. To do so, I’d like to use the masterpiece that was Mean Girls.

Those Sacred Lunch Tables

The 2004 film Mean Girls follows the struggles of teenage girl Cady Heron, who’s trying to navigate an American high school after being homeschooled in Africa for most of her life.

For our purposes today, I’d like to focus on one scene in particular: when Cady’s new friends (Janis and Damian) introduce her to North Shore High’s social groups. (If you haven’t seen this movie, please watch the clip below. Everything I’m going to say afterward will make A LOT more sense.)

At North Shore High, there’s a well-defined, obvious, and oppressive social hierarchy. As Janis explains:

“Where you sit at the cafeteria is crucial because you got everybody there: You got your freshmen, ROTC guys, preps, J.V. jocks, Asian nerds, cool Asians, Varsity jocks, unfriendly black hotties, girls who eat their feelings, girls who don't eat anything, desperate wannabes, burnouts, sexually active band geeks, the greatest people you'll ever meet, and the worst. Beware of the Plastics.”

Now, early 2000s “edgy” (read: racist, homophobic, and misogynist) humor aside, I still think about that list. Because when I went to an American-style international school in the Philippines, we had a social hierarchy just about that rigidly confined to lunch tables (if not more).

Like in Mean Girls, we had the silly freshmen and new students who didn’t know how to fall in line yet; nerds; cool athletes (popular guys); lame athletes (they played badminton or something else not “sexy”); party girls; desperate wannabes; burnouts / people who got bad grades; band and drama geeks; popular girls (aka “the Plastics”); and then the outcasts… (aka me).

I’m sure there were so many other nuances that I can’t quite recall, but one thing was for certain: where you belonged was defined by where you sat at lunch, and you never broke the rules. Because if you sat somewhere that didn’t match your “status”, you would immediately be relegated to the “desperate loser” category. The only thing worse than being unpopular was being unpopular and not knowing it. You always had to know your place.

Lunchtime was when those social hierarchies were established, asserted, and demonstrated most clearly. Because at other times we were either forced to mingle between social groups in classes and extracurriculars, or there weren’t enough people populating any particular part of the school campus to properly separate out by status.

So if you were in-between social levels, you might have gotten away with talking to someone more popular in the hallway or while waiting for the school bus… but you’d never risk “mingling” at lunch. At most, you might have been granted the permission to exchange a few words in line for food or (if you were really lucky) the popular kids could have waved you over to stand by their table and answer their questions as they judged you.

To this day, I think the most unrealistic part of Mean Girls is that the queen bee Regina George actually invited Cady to sit down.

Threads: The Social Media Cafeteria

Think back to that fictional cafeteria from Mean Girls. Really imagine all of those social groups and their implied level of influence compared to the others. Can you see them in your mind’s eye?

Now, open Threads.

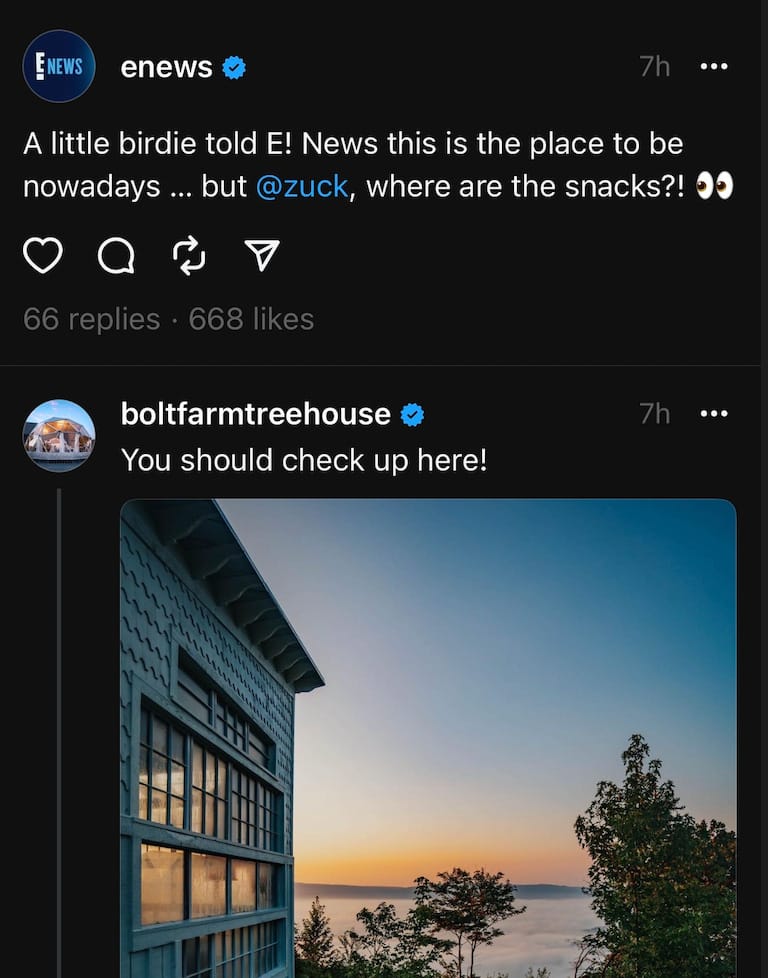

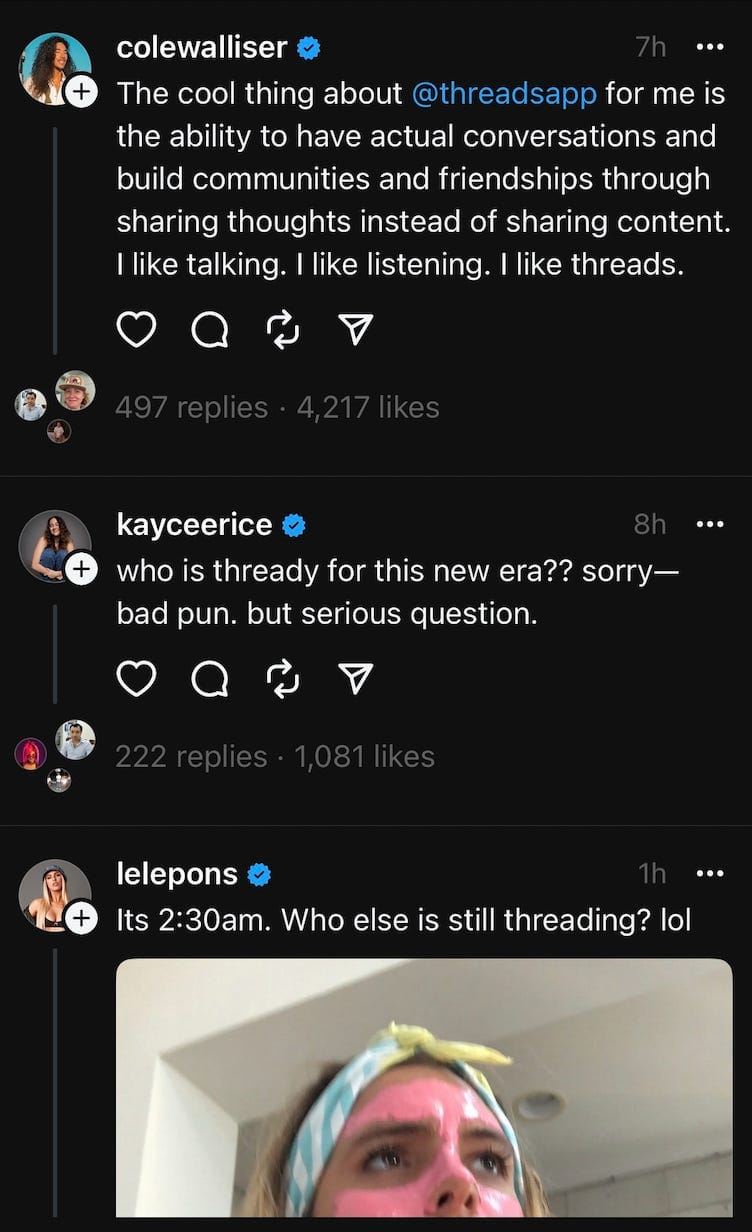

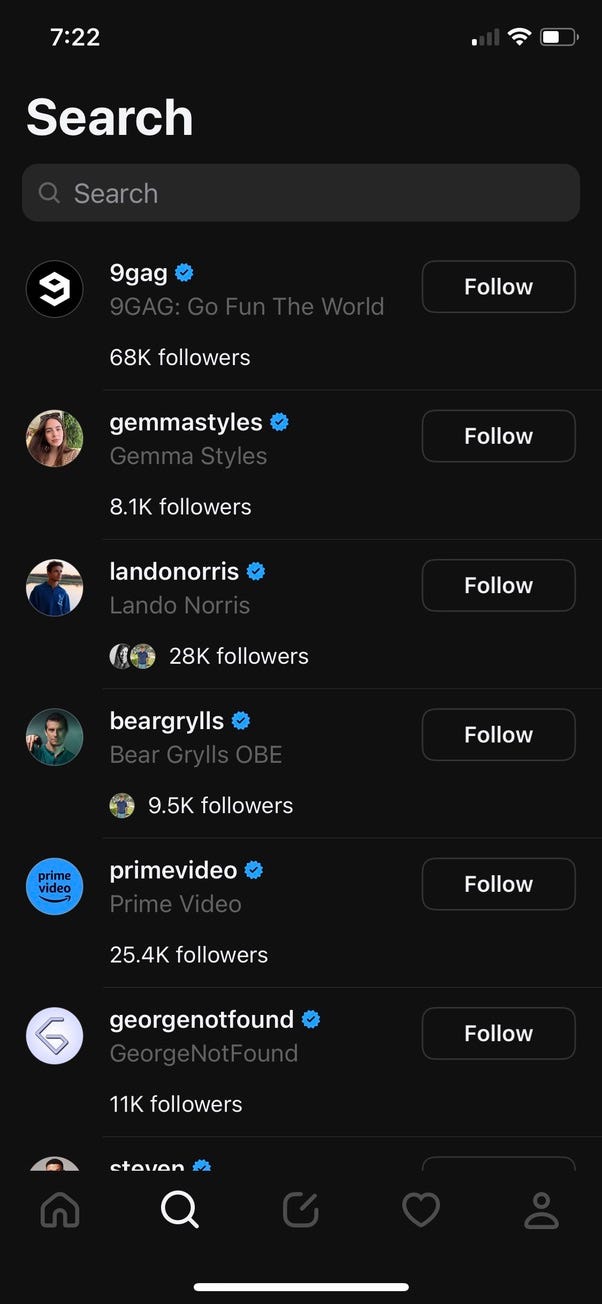

If you don’t have an account, don’t worry. I’ve been collecting screenshots from my feed ever since the app first launched, so here’s your taste of the madness:

This feed will haunt my nightmares for a long time.

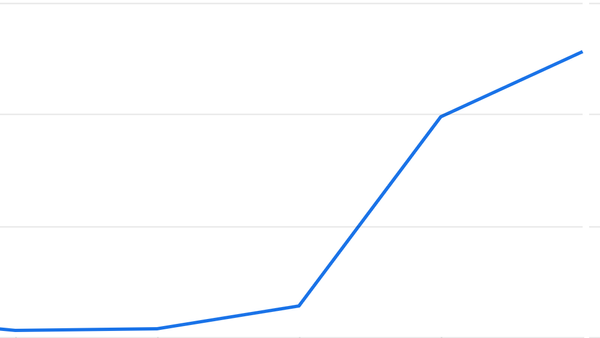

As everyone has already pointed out, at launch this app was already flooded with celebrities, influencers, and big brands. Supposedly, this was to pre-populate the app with content. In practice, however, all this did was create a firmly established social hierarchy. If you were already big elsewhere, then you could get the early invite and algorithmic boost, or you could at least port over a fair chunk of your followers from your Instagram account.

And if you think I’m being dramatic, comparing follower counts on some silly app to high school social hierarchies… I’m not the only one. Here are just some of the posts that landed on my feed talking about that same uncanny feeling:

Come on, this sounds exactly like teenage gossip:

The people who already had status on Twitter or Instagram are getting to keep that status. Instead of truly resetting the playing field, Threads firmly maintained the same hierarchy that was already established everywhere else. This app never felt new.

From my first minutes there, Threads felt stale and depressing. The algorithm is already set to reward the people who got algorithmic boosts and distribution everywhere else. The feeds are recommending those with the most influence, and new accounts will have to work extremely hard to gain any traction.

Instead of a true level playing field, Threads greeted each new user with a glossy copy of the North Shore High cafeteria map: here’s where you will be sitting, and that’s where we’ve put the popular kids. Sorry, no mingling.

New Platform, Same Status

Many before me have already complained about how boring all of those celebrity and brand posts really are. I mean, come on: how many times can Wendy’s make the same jokes before you throw your phone at the wall?

The poor content quality from big accounts is not even remotely surprising. It’s the same pattern we’ve seen elsewhere… including with the one person who will probably never make a Threads account: Elon Musk.

As Ed Zitron wrote back in April 2022, Musk was never good at Twitter. His posts have always been crap and mediocre, filled with boring nonsense and stolen jokes. Yet, he had a gigantic following long before he bought out the company. But why?

Simple: he never had to try. In Ed Zitron’s words:

“Musk’s old tweets used to be dorky and boring, and they’d still get tons of engagement. If you have millions of real people following you - something that happens when you’re a multi-billionaire that runs several companies, one of which (Tesla) had a completely complicit and docile press following for the best part of a decade - you can say anything, and they will react to it.”

The size of your following is often correlated to your power outside that platform (most big accounts are celebrities, billionaires, journalists, or media personalities for a reason). And the amount of effort that you need to invest into your posts is inversely proportional to your following size.

If you’re small, you will only get noticed by making really great content and having some luck with the algorithm. If you’re big, you can kind of get away with posting mediocre garbage. Simply thanks to exposure to so many people, your posts are much more likely to get surfaced via any algorithm. And then the cycle continues.

But here’s the beauty of the internet: because so many of us would end up posting on the same platforms as those celebrities and big personalities… sometimes we’d have a shot. Over the years on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, what-have-you – occasionally some regular person would strike gold and get that algorithmic blessing. They’d pop off with one viral post or continue compounding on previous momentum to grow big. It’s a digital rags-to-riches story, one of the last remaining frontiers of the increasingly impossible American Dream.

So, what happens to that dream of digital meritocracy when a brand-new social media platform is launched with those old hierarchies firmly rooted in place?

Why Are We on Social Media?

Whether you think Meta’s choice to preserve social hierarchies on Threads is a problem depends on how you view social media.

The two words in that name are in conflict with each other: “social” implies bidirectional interaction between people, while “media” suggests some type of broadcasting where a few speak to the many. And I see that tension in the history of these websites, at least ever since MySpace.

It’s “Media”

Some users have been defending Meta’s choice to fill Threads with celebrity posts. They argue that most people like keeping up with celebrities and want to use social media to do so. They get to poke around in a celebrity’s comment section and send a message, with the non-zero (but still minuscule) possibility that the celebrity might notice them. Parasocial relationships are fun, after all.

You could also defend the “media” side of things by pointing out how much social media has been used to keep up with current events. Whether sports or revolutions, Twitter used to be king for keeping up with the world in real time. Unfortunately, Twitter’s rate limiting has broken that. And Threads doesn’t even have a chronological feed. (But Mastodon has recently become decent for following current news, as I’ve inadvertently stumbled into with my own account.)

Yes, the broadcasting relationship has its perks and utility. But do we really want our apps to replicate the same power dynamics as “mainstream” media? After all, one of the reasons the internet took off was because people were tired of hearing the same perspectives from the same five people on their TV screen. Mainstream media can be wonderful, but the beauty of social websites was that they also opened up the floor to some alternatives.

As most marginalized people would probably agree, the mainstream often ignores or twists narratives focused on marginalized experience. I’m not a person of color, so I cannot speak to that dimension of things. But I am a queer immigrant with an extremely stigmatized psychiatric diagnosis. I don’t typically see myself represented at all, let alone empathetically, in mainstream sources.

Having a plurality of voices is essential to a democracy (while still maintaining good moderation, of course). We need to have a level playing field between more popular and niche media sources, both for access and integrity.

It’s “Social”

Isn’t social media there to help us connect with people?

You might think that Threads has done the best job with that task out of any other Twitter alternative. After all, there’s now more than 100M users there and importing your followers or follows from Instagram is just a couple of clicks.

But I disagree with you. Because social media is not there just to connect with people you already know.

If that’s what you’re looking for, then you have much better tools: group texts, WhatsApp, Discord, Slack, a private message board, a giant Zoom call. Why would you post every interaction with your friends to the public, where an algorithm could take an innocent inside joke and plop it in the feed of a potential malicious party?

Instead, social media is there to help us do something much more nebulous, yet also more important. Social media helps us discover new people. Social media is one of the easiest ways for people in 2023 to make new friends. Social media is a way of connecting us to the wider world and embedding us in a social fabric beyond our nuclear families and office buddies.

I’ve made so many of my friends on social media. When I was little, I didn’t know anyone who shared my interests in “real life”, so I found communities online. I was 8 years old earning badges on a Sims 2 forum, and I loved every single second of it. I ended up learning how to make custom skins and mods for the game, and even submitted some decent stuff to that forum by the time I turned 10. I contributed something of value and had a crapload of wonderful conversations with people ranging from 8–80 years old (okay, I think the oldest person there was closer to 50. But still!)

Even now, most of my friendships after college have been through social media. I didn’t know any marketers back in Ithaca, where I lived for 2 years. I didn’t really talk to anyone except my husband’s law school friends and my family. And that was fine – because I was making plenty of friendships online.

I’ve met multiple of those online friends in person, and we had a wonderful time. Some I communicate with regularly purely online, and yet they are some of the most precious connections. I sincerely love some people who I met because of social media. And I wouldn’t have gotten to experience that love if an algorithm somewhere didn’t surface some posts on my feed.

Social Media is Made by the People Who Use It

Look, the value of social media is in the people who use it. Us. We are the true value of any platform.

I wrote about the game Disco Elysium last week, but I want to bring it back to discuss one of my favorite mechanics within it. You see, Disco Elysium is an RPG and one of the ways you can customize your character is by investing points into developing certain skills. Pretty typical of video games in that genre, except the skills are relatively unusual.

One of those more unique skills is “Shivers”. The game describes it as:

“Raise the hair on your neck. Tune in to the city.”

Essentially, if you invest in Shivers you’ll be able to feel the city around you. As you walk around in the game, you’ll get clues as to what memories each place might hold. You develop an intuition for the history of every seemingly inconspicuous corner.

The knowledge that Shivers grants you stands in stark contrast to a similar but more familiar skill called “Encyclopedia”. This one is described as follows:

“Call upon all your knowledge. Produce fascinating trivia.”

Encyclopedia will also grant you facts about the city. They will sound like well… entries in an encyclopedia (that’s a paper Wiki, for all of you non-existent Gen Z readers). Or, if that’s more your preference, like a basic SEO article. “What is concept?” And that type of thing.

The YouTuber Jacob Geller described the difference between them beautifully:

“The difference between Encyclopedia and Shivers, these two ways of knowing the city, is the difference between a historian who’s studied New York for decades, and a taxi driver who’s traced the streets for the same amount of time. Both are valuable, legitimate ways of knowing a place; but while the historian’s knowledge can be categorized and quantified, the driver’s feels more ineffable. They might understand the city less a series of events and more as a bloodstream.

The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the banisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.”

I’d say that “Encyclopedia” means understanding a place with the brain, while “Shivers” is understanding a place with the heart. Who’s lived here before? How did they feel when they walked down this street? What were they dreaming about or scared of? Am I like them in any way?

And here’s why I’m telling you all of this: I think these ways of knowing can be applied to digital spaces just as much as physical ones.

What is the “feel” of a social network? Its bloodstream is the flow of all the content that the users produce over the days, months, and years. Its pulse is the meaning created from those spontaneous connections and ideas. Its beating heart is a synthesis of all the people who live out sections of their lives on its pages.

We, the people, are the soul of a social network. It’s not the features, it’s not the size, it’s not the corporation that owns it. The soul of any social network is made up of its users and what they choose to post or interact with.

And in that way, Threads is cutting out the most valuable part of all. We’re all forced to look at our social media as “media”, diluted to its lowest common denominator or highest Total Addressable Market (number of people who might be interested in seeing it).

But Threads preserved only the vile hierarchies of other networks. It cannot preserve the soul because its soul will never belong to a single website.

Where to Next?

I don’t blame anyone who flocked to Threads to find their internet friends. I’m on there too, and it’s been exhilarating finding old faces again who I haven’t seen since leaving Twitter.

But I also feel like Threads is pulling a bait-and-switch on us. They drew us in with promises of new connections and reach, then left us with little more than Instagram with a fresh coat of paint.

Blissful ignorance can be pleasant, but the world is kind of burning down. I don’t think preserving divisions, class hierarchies (digital or otherwise), and monopolies is going to help anybody in the long run. We lost the connections we made on Twitter or Reddit because some rich guys got too greedy. Because they viewed us as “data” to be held captive, not humans who create value just by existing on their sites.

The future for Meta is, I hope, in the Fediverse. It won’t be easy, they’re definitely not ready now, and we’ve got a lot to figure out in how to actually pull that off without hurting the Fediverse with a flood of spam, far-right grifters, and corporate puns.

But I firmly believe that a better internet for all of us is a more fragmented but interoperable place. Because that’s the way for us to reclaim control over our digital lives without losing the connections that made our online existences worth it.

As Cory Doctorow wrote in his essay about Threads and giant social platforms:

Meta was able to do this because it owns both Threads and Instagram. But Meta does not own the list of people you trust and enjoy enough to follow.

That’s yours.

Your relationships belong to you. You should be able to bring them from one service to another.

Don’t let any corporation convince you otherwise.

Self-Promo Aside:

Hi, in addition to writing this newsletter, I also run a marketing agency for B2B tech brands. If you’re interested, we’re currently accepting one more new client.

Musical Minute

Stevie Nicks - “Edge of Seventeen”

I’m in love with this song. I don’t know why right now, but I can’t stop listening to it. And I guess some lines can apply to opening the Threads app:

“Well, I went today

Maybe I will go again tomorrow

Yeah yeah, well, the music there

Well, it was hauntingly familiar”

Top 3 Reading Recommendations

For this piece, I read a lot of articles from other people analyzing Threads. I might write something more thorough in response to them later, but here are the best ones for you:

- “Twitter Alternatives: Mastodon, Post.news, Threads, Bluesky, and others” by Teri Kanefield.

- “The Whitening of Social Media” by Shay Stewart-Boule.

- “The algorithmic anti-culture of scale” by Garbage Day.