Platform Responsibility: In Defense of Geraldine DeRuiter

Geraldine DeRuiter's new book "If You Can't Take the Heat" is brilliant. But The New York Times chose to publish a review attacking her instead. Here's why that wasn't okay.

If you publish content online, you’re responsible for the harm that it may cause.

And if you have a large, influential platform - your responsibility grows relative to the level of influence. A 13-year old posting a conspiracy on her private Instagram account to a circle of five close friends is objectively less dangerous than a TV anchor repeating the same conspiracy to 5,000,000 viewers.

Sounds simple, right?

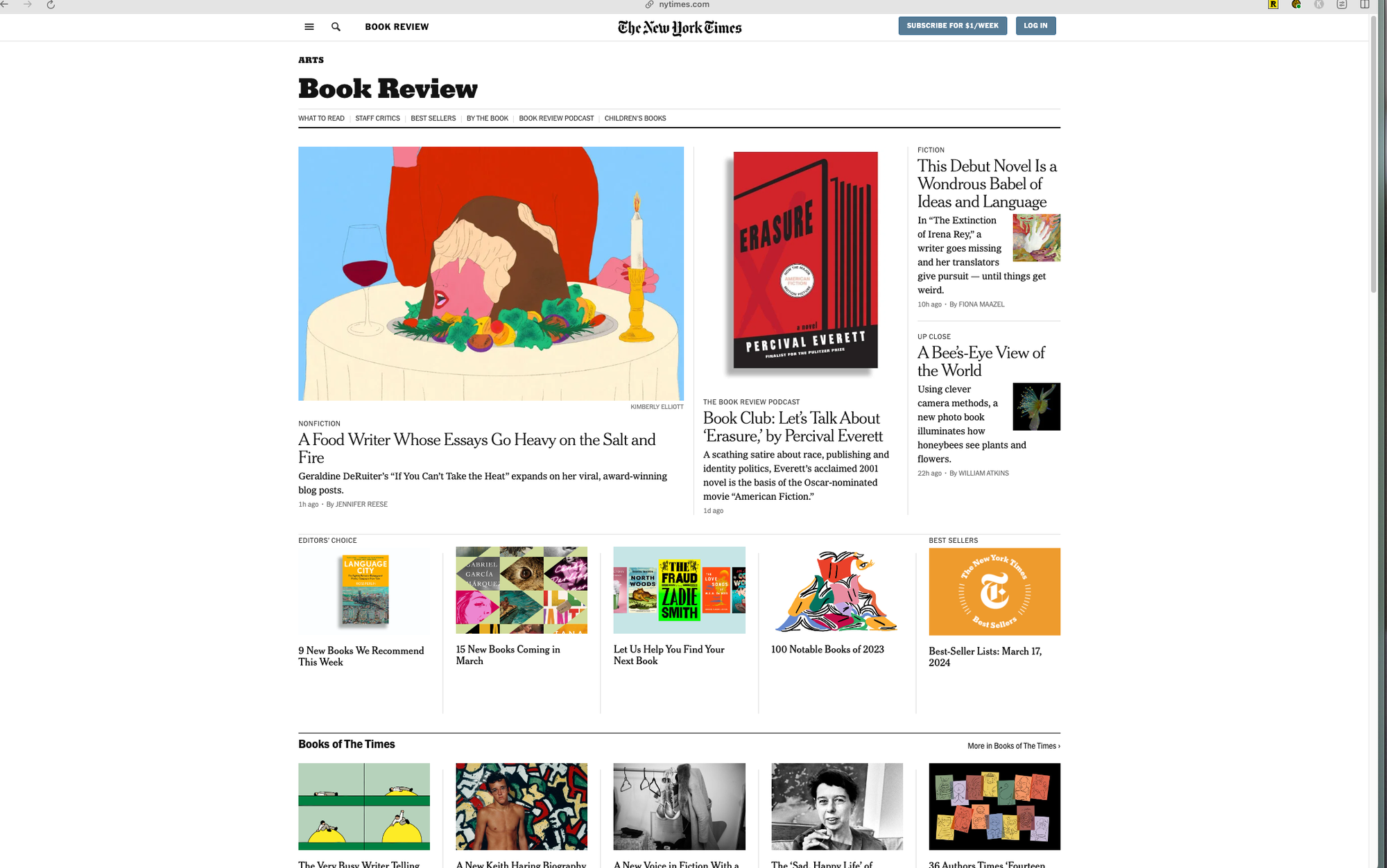

Well, it seems like The New York Times didn’t get the memo. Because today, on March 9 of 2024, they published one of the most abhorrent and mean-spirited articles I’ve ever had the displeasure of seeing on the internet.

I’m talking about Jennifer Reese’s awful review of “If You Can’t Take the Heat” by Geraldine DeRuiter. DeRuiter, if you’re not familiar, is a hilarious food and travel blogger and also one of my favorite authors. She’s a beautiful, intelligent, hilarious woman. And her second book, about “food, feminism, and fury” is coming out this Tuesday.

So how did The New York Times, one of the world’s most famous and well-established publications, choose to review DeRuiter’s new book?

By illustrating her decapitated head on a plate, getting devoured by another woman. No, I’m not joking.

Post by @theeverywhereistView on Threads

Needless to say, most people who have eyes will recognize that graphic as fucking unacceptable. It’s violent, vile, and vicious. But yet... here it is, staring at us from the top of the NYT book review section:

How does something like this get written, published and approved? Through a systemic failure of digital creators and publishers to empathize with their subjects and intended audiences.

I believe that neither Jennifer Reese nor the New York Times stopped to consider that DeRuiter is a human. And that problem isn’t isolated just to this review – it’s shared by the entire internet.

We’re all complacent in failing to recognize the responsibility that should come with having an online platform. And as with any avoided responsibilities – when we look away, someone gets hurt. Too often that someone is a representative of an already disenfranchised group – like women who write about feminism.

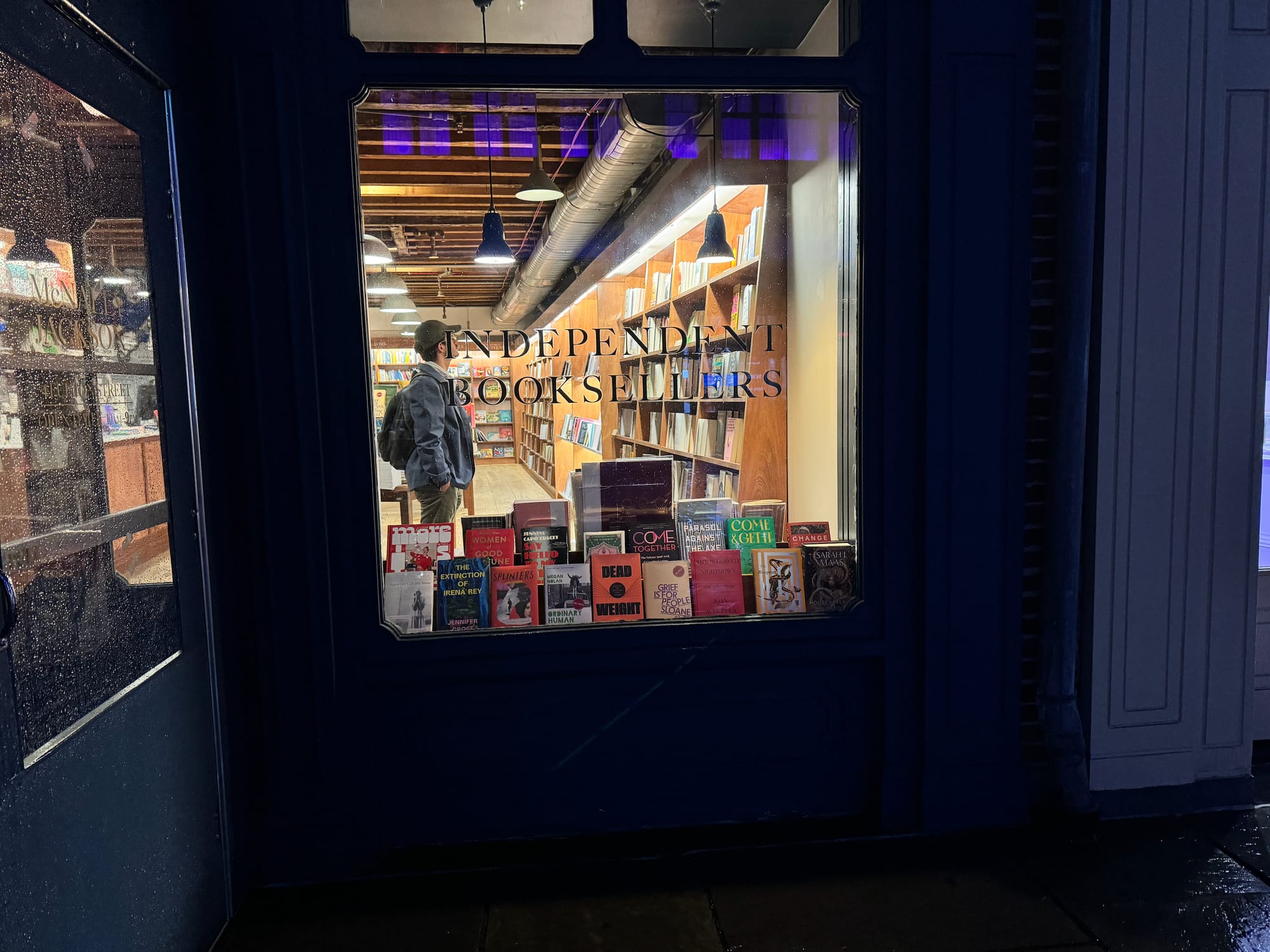

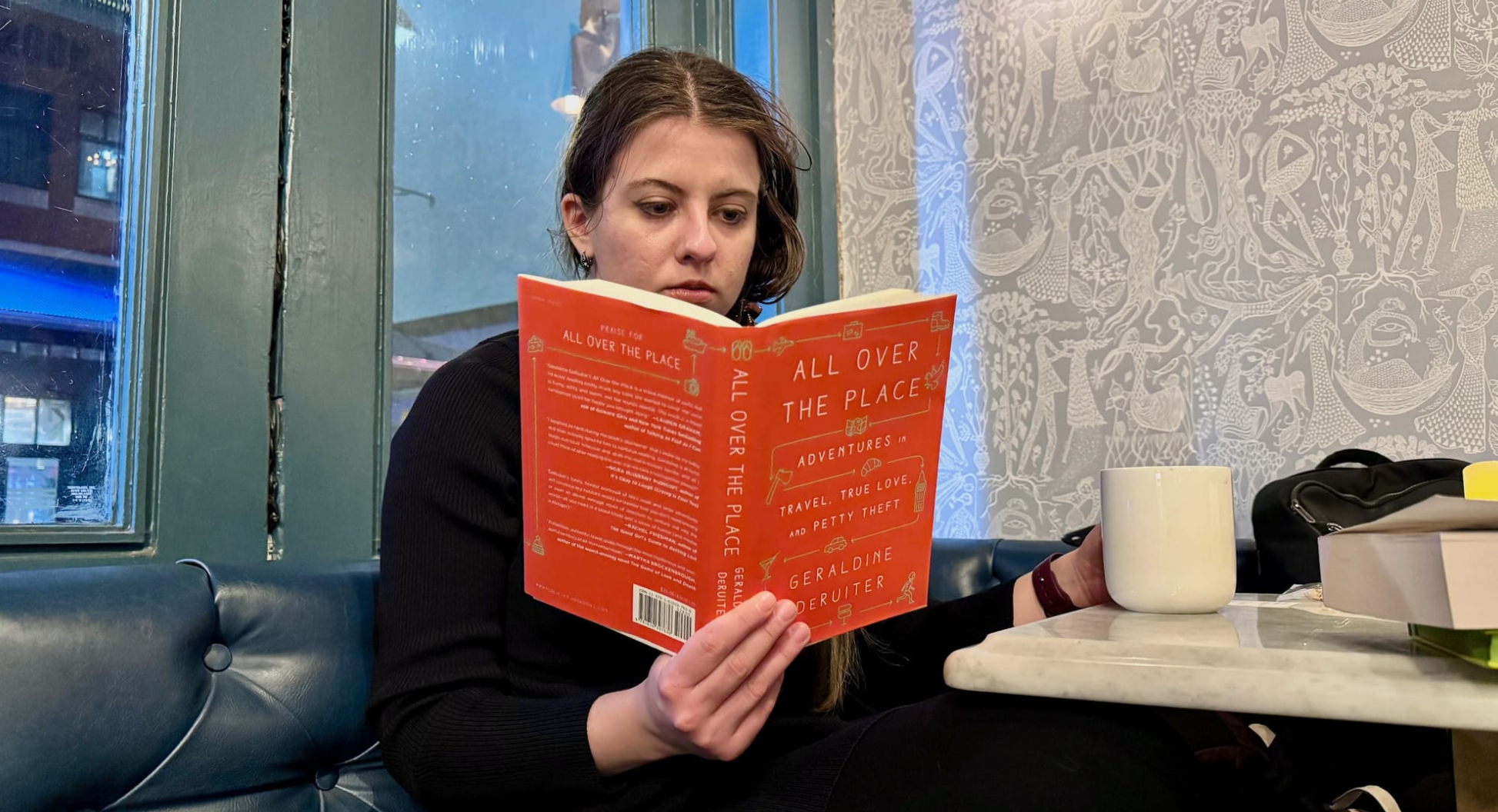

And to prove my point, I decided to wear a dress, put on makeup, and head to my neighborhood McNally Jackson here in Downtown Manhattan.

Why We Hate Hot Girls Who Read

I dressed up to call attention to an interesting phenomenon – as a young, pretty (I think), and white woman living in New York City, I belong to a demographic that has a strange relationship with books.

When women like me read in public, we can be seen as doing it “to look cool”. Books, love of literature, and an affinity towards bookstores get perceived as fashionable when associated with beauty.

Why? Because true diversity of opinions is scary.

“The noise of argument, the constant hum of disagreement—these can irritate people who prefer to live in a society tied together by a single narrative.” – Anne Applebaum, “The Twilight of Democracy”.

One uncomfortable fact about living amongst other humans is that we prefer to live in different ways to one another. Disagreement is simply part of human nature – whenever humans can freely express themselves, they’ll also argue. Those disagreements are often how we can learn and grow, changed by unfamiliar ideas; but they are also stressful. A life in conflict is exhausting.

So, if want to live in a society where people don’t argue so much – how would you do that? I see three ways:

- Remove yourself from the wider world and interact only with people who agree with you.

- Sabotage anyone who disagrees with you by painting them as “untrustworthy” to others.

- Limit others’ access to information, showing them only ideas that you agree with.

All around us, some people choose one of those three paths. Instead of embracing a free life as necessarily a bit chaotic, they force simplicity on those around them.

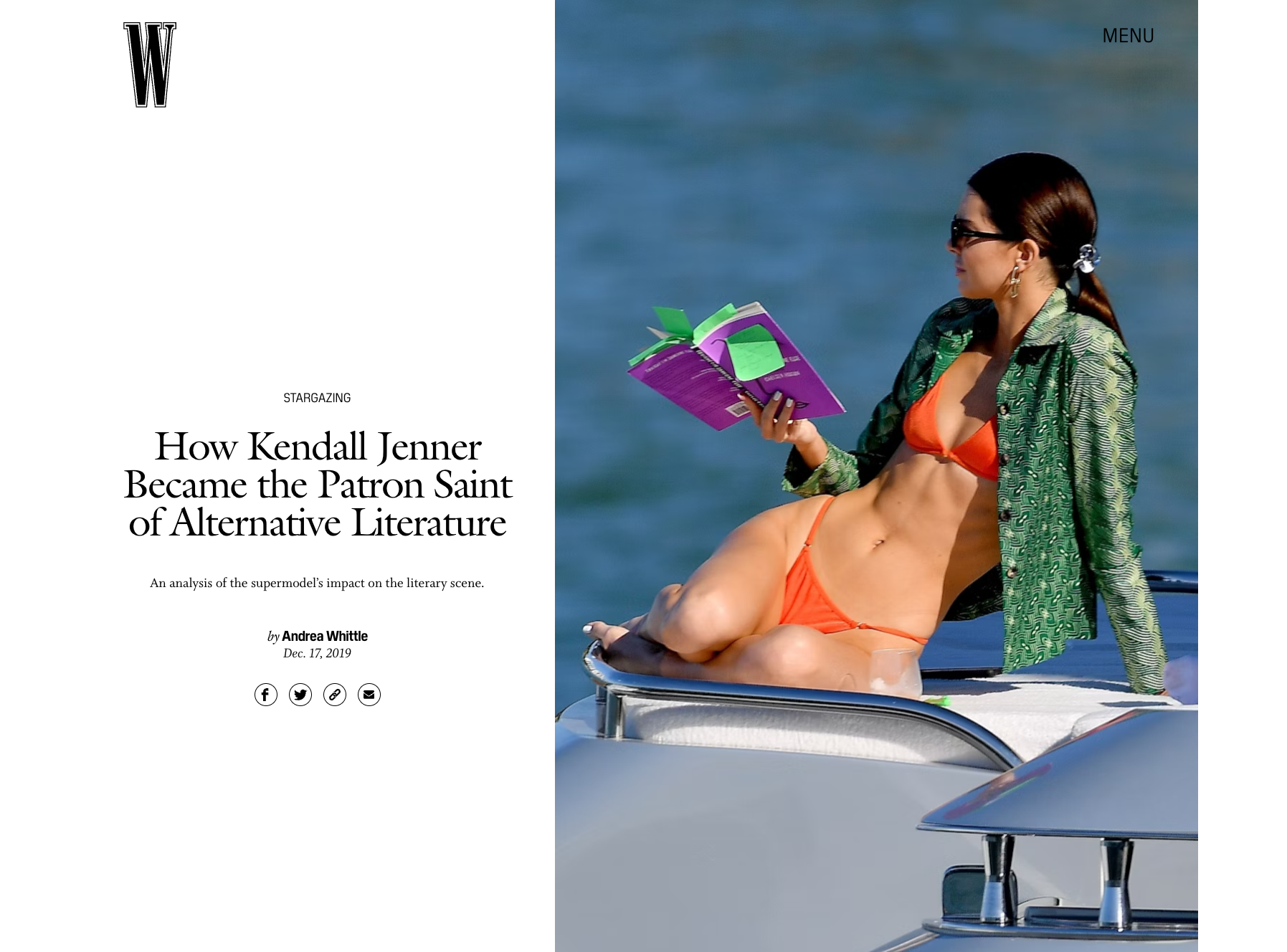

To demonstrate how this works, let’s consider the hot girl who reads. The Kendall Jenner, Reese Witherspoon, Dua Lipa, or many an online influencer who posts a photo or video of herself in a beautiful outfit holding a book.

The hot girl who reads is often the subject of anger and disdain. For example, if you Google “booktok”, the book review community of TikTok that’s largely dominated by pretty, young women, then you’ll see titles like “Is BookTok sucking the joy out of reading?“, “How can reading make you dumber? BookTok makes that possible”, and “BookTok is ruining books”.

We’re suspicious of beautiful women who express their love for books or take photos of themselves flipping through pages. Books are viewed as a symbol of fake intellectualism, a way to rebrand one’s image.

How real is that suspicion, though? Faking an interest in books seems like a lot of effort for what it’s worth. As explained by The Guardian:

“It is easy to be cynical about the depth of some celebrities’ engagement, but it is hard to fake a genuine response to a book you haven’t read – plus, in front of millions of followers, they put themselves at risk of being caught out.”

Suspicion of the Female Reader

Yet, we continue to be threatened by girls and women who read. And that fear isn’t new. As Mina Le explains in her excellent video essay about “the hotgirlification of reading” – when dime novels made reading popular with women in the 19th century, certain authors hated it, “believing that the degradation, aka the feminization, of literature was impacting the success and prestige of their own work.”

As we’ve just passed International Women’s Day, I’d like to remind you that, unfortunately, women are often an oppressed group. And as with many other disenfranchised demographics, women often end up restricted in their access to reading. After all:

“Reading is both the result of human evolution and a major actor in its cultural explosion. The expansion of this ‘cathedral’ of the mind, our prefrontal cortex, allowed our species to come up with writing. This invention, in turn, sharpened our minds. Its exercise endowed us with additional external memory that allows us, as Francisco de Quevedo put it, to ‘listen to the dead with our eyes’ and share the thoughts of past thinkers.” – Stanislas Dehaene, “Reading in the Brain”.

Reading and writing makes us smarter. And women who read or write are dangerous, because they are women who might disagree with the status quo.

Is it even surprising that a review of a book about “feminism, food, and fury” tries to question the intelligence of that book’s author? When Reese talks about “significant gaps in DeRuiter’s skill set” or how DeRuiter “writes with typical theatricality” – those jabs at literary competency are really an attack on a woman who dares to disagree.

It doesn’t matter that Reese is also a woman. She hates DeRuiter’s book for the same reasons that misogyny has always hated women – daring to have a voice. How else can you explain quotations like:

“DeRuiter has an “all eyes on me” narrative persona — ravenous, pugnacious, irrational, loud. Unmodulated, her voice is ideal for delivering a rant, but it can overwhelm less flammable material.”

Suspicion of the Female Writer

What’s worse than a woman who reads? A woman who writes.

To write about pain and suffering you need to understand it. As Melanie Brooks says of the memoirist Sue William Silverman:

“This memoir’s very existence is comforting proof that Silverman doesn’t need me to rescue her. She is already safe. How else could she have spoken the unspeakable with such astounding artistry and grace? Without knowing her, I am certain that, though the powerless, victimized girl will probably always dwell somewhere inside of her, the woman Silverman has become is a resilient and extraordinary courageous survivor.”

The writer controls the story they tell. The female author is a female storyteller, in control of her own narrative within the words that she writes. To write is to move past thinking of yourself as a victim. To write is to claim power.

Reese understands this. Her review is particularly upset that DeRuiter dares to be angry:

“One of her overarching gripes — a rightful gripe — is about the way women blunt their anger and soften their voices in order to placate and please. But women can also soften their voices in order to persuade and illuminate. But rather than exploring this tranquil space with delicacy and gentle wit, she swamps it with salty all-caps asides and sarcastic mini-diatribes.”

In essence, Reese is telling DeRuiter to shut up and sit pretty. Being upset about the state of women in society is okay, but expressing that should only be done “with delicacy and gentle wit”. Speak truth to power, but don’t be too threatening.

It seems that Reese wishes that women like DeRuiter would only ever whisper, rather than speak.

Audiences Matter

What is the difference between writing for yourself and writing for an audience?

The presence of an audience, of course. A fact so simple that we often gloss over the implications. Because the mere existence of other humans who are expected to read a piece (or interact with any other type of content) fundamentally changes the purpose behind the act of creation.

As Kai Tempest writes in “On Connection”:

“Words on a page are incomplete. The poem, the novel, or the non-fiction pamphlet are finished when they are taken up and engaged with. Connection is collaborative. For words to have meaning, they have to be read.”

Except so often, as people who work with creating content on the internet, we forget about our readers. We think only of ourselves, our messages, our goals.

We want to “distribute our brand”, “gain awareness”, or “improve sales”. We imagine our pieces as complete the moment we hit “publish”. The content is imagined as if it is complete and perfect in the moment of its creation. We get upset with algorithms for not showing our content enough, complain about a lack of engagement, try to hack traction.

But let’s pause for a minute. What happens when a new person encounters our content?

The words we’ve created are reborn in the moment that they are perceived by another. The ideas we expressed are understood through the experiences that the reader has had in the past. The thoughts we shared merge with new thoughts that we couldn’t have predicted or controlled.

Any act of communication is also an act of entropy. Randomness is always present when two humans interact. And all content changes its meaning depending on who is reading it and when.

Reading is Always Personal

We ourselves also change as we read:

“The arts [..] trigger the release of neurochemicals, hormones, and endorphins that offer you an emotional release. When you experience virtual reality, read poetry or fiction, see a film or listen to a piece of music, or move your body to dance, to name a few of the many arts, you are biologically changed. There is a neurochemical exchange that can lead to what Aristotle called catharsis, or a release of emotion that leaves you feeling more connected to yourself and others afterwards.” – Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross, “Your Brain on Art”

When a work of art means a lot to us, we can feel as emotionally invested as if we’ve personally known its creator. Just as for the people we love, we can make sacrifices for the works of art that we love too.

When I decided to live out the stereotype of the “hot reader girl” earlier today, I had to walk through pretty miserable weather – the Financial District was showered with cold rain and icy wind this Saturday evening, and yet I made my way to the neighborhood bookstore.

Why did I do this for a newsletter essay to defend Geraldine DeRuiter?

Because I can’t talk to her directly. Reading her books is one of the only ways that I can still connect with this intelligent, hilarious, wonderful woman who reminds me so much of myself.

As Harold Bloom describes in “How to Read and Why”:

“Reading well is one of the greatest pleasures that solitude can afford you, because it is, at least in my experience, the most healing of pleasures. It returns you to otherness, and as such alleviates loneliness. We read not only because we cannot know enough people, but because friendship is so vulnerable, so likely to diminish or disappear, overcome by space, time, imperfect sympathies, and all the sorrows of familial and passionate life.”

So reading DeRuiter’s work is, to me, a magical act. It takes me out of my overwhelming loneliness and lets me feel, even for a moment, that this woman who I so desperately wish I could talk to, is telling these stories and jokes just for me.

And while my personal circumstances are specific to me alone, I am also every reader. Because we all read out of loneliness. We all read to become a little more than ourselves. We read so we can bear to be alive.

There’s a strange inequality inherent to telling stories. I might not be part of DeRuiter’s life, but DeRuiter IS part of my life. She speaks to me whenever I open her book or pull up a page of her blog. DeRuiter is another human being, with her life and free will, existing in a different place on this earth. Yet when she writes and her content ends up in a place that I can access, I can suddenly access a part of her soul as well.

Very few things in the universe are as precious as the gift of communicating across space and time. Content is a miracle. Content is, whether we like it or not, art.

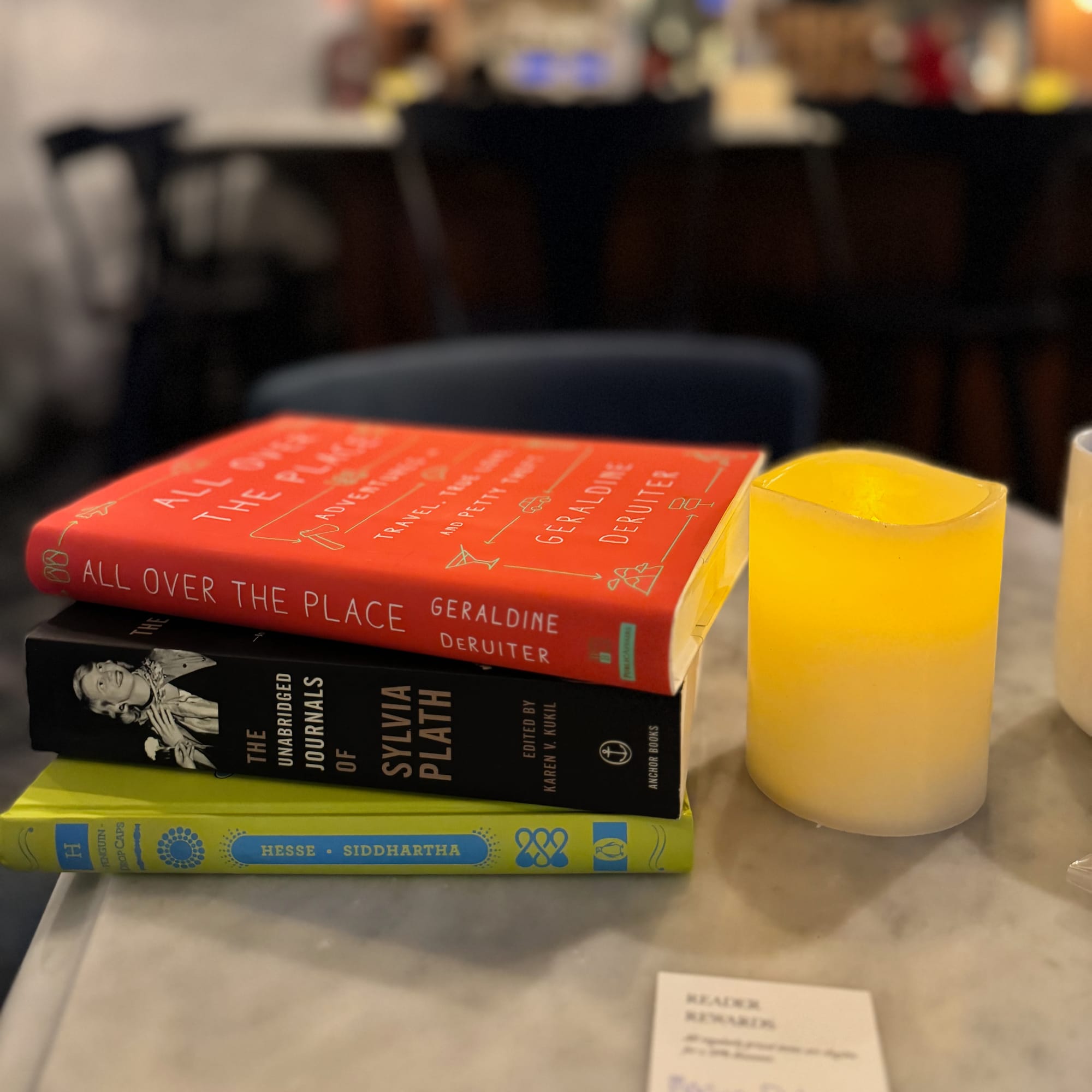

I’ve searched for DeRuiter’s first book in every bookstore and library I’ve walked into since February 2023. I always look for her name in every section that could possibly include it: autobiography, memoir, essays, travel, feminism.

And as I walked around McNally Jackson today, three days before the scheduled release of DeRuiter’s second book, I felt a deep pang of fear. What if I come back to this bookstore on Tuesday and DeRuiter’s book is nowhere to be found? What if they don’t find a place for her name on the shelves? What if I don’t see that bright shade of pink beckoning me from a single wall of my favorite store?

After a while, I bought myself a frequent reader card and asked the cashier if they were planning to stock DeRuiter’s book. “It is coming out,” the employee told me after typing something into their computer. “But we aren’t planning to stock it. Would you like me to order one for you?”

I thought about it. I’ve already bought DeRuiter’s book twice - pre-ordering it as a Kindle and a hard cover on Amazon. Did I really need a third copy?

“Yes, please order it,” I said.

I guess I’m starting a collection.

Books and Empathy

Books are so powerful because they connect us with others.

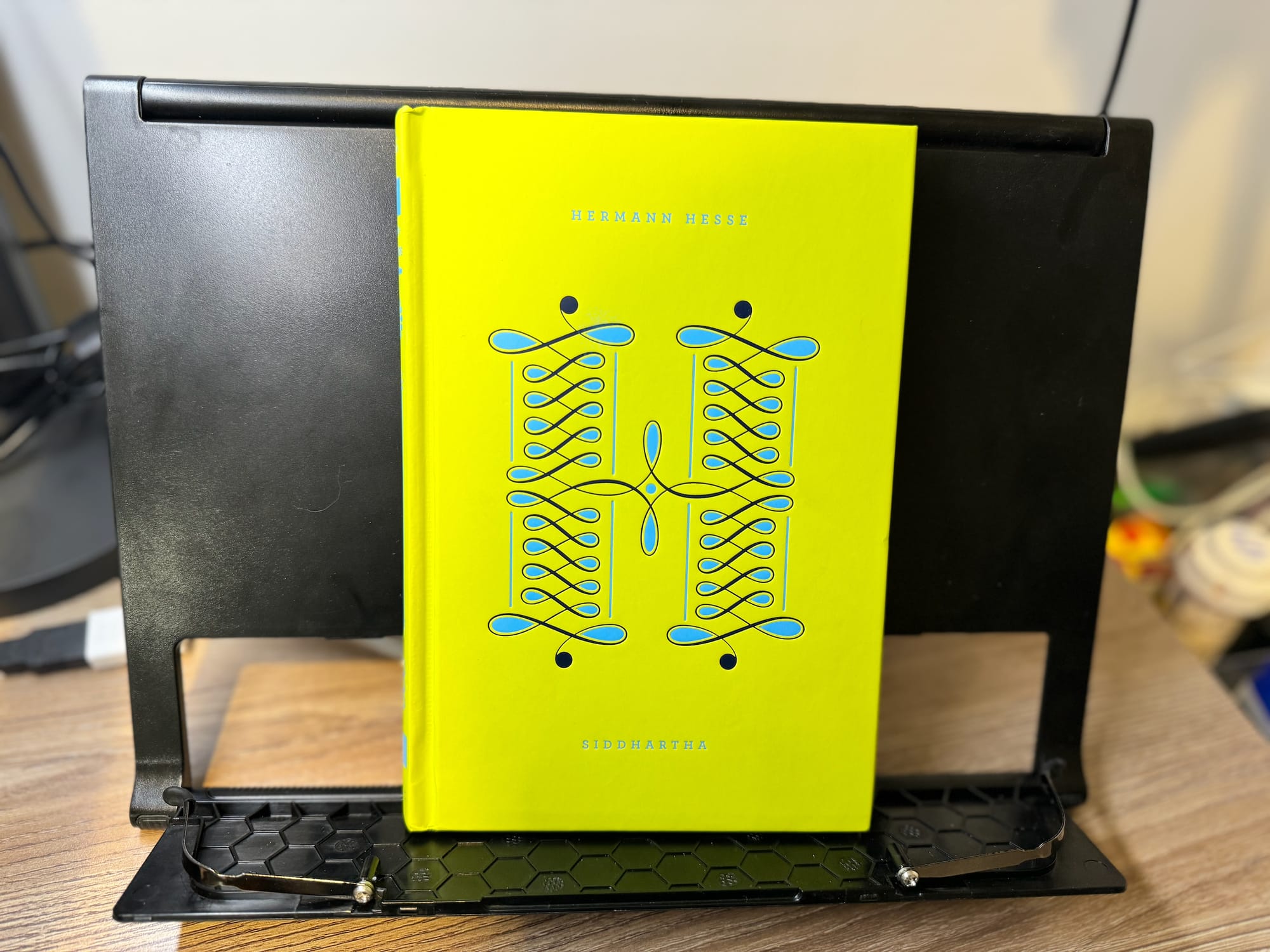

Just this week, a coworker and mentor whom I love very much sent me a book as a gift. He lives in Europe, and I haven’t even met him in person. But he went on a website, entered my address, and ordered this book to be mailed to me.

And once the package arrived yesterday, I held a physical reminder of this person who means so much to me. I thought of him picking it out, checking delivery details, and wondering what I’ll think of it. In the past 24 hours, I’ve carried that book everywhere with me, reading bits and pieces whenever I can.

The words on those pages have now become a symbol of connection between me and my coworker. The thoughts and feelings of Hermann Hesse, its author who is long dead, are now a vehicle for communicating between two people whom Hesse could have never met. This writing of a German-Austrian man is now being shared 100 years later by a man in a different country with a woman living on the opposite side of the Atlantic. And if you go read that book because of my newsletter, that’s another whole brain and life touched directly by some dude who sat and made up a story in 1922. How wild is that?

“You are stripping yourself. You are exposing your life, not how your ego would like to see you represented, but how you are as a human being. And it is because of this that I think writing is religious. It splits you open and softens your heart toward the homely world.” – Natalie Goldberg, “Writing Down the Bones”

And this religious experience gets bastardized when we forget about connection and think only of traffic.

The Problem with Online Traffic

“When we see ourselves distorted in the media mirror, we should probably consider that some of what we see is actually us. We’re seduced by celebrity stories. We enjoy a good car chase. And who doesn’t take guilty pleasure in the refreshing saliva spray of a commentator spouting our views?” – Brooke Gladstone, “The Influencing Machine”.

When we look at online content, we can get a false sense of protection from the glass screens separating us from the people who we might be discussing or learning about. For Reese, DeRuiter wasn’t a real human being sitting near her in the same room. Instead, DeRuiter was an abstract figure who produced a book that Reese didn’t like. So the review assumed a false air of objectivity – discussing the book as if the author would never see it, as if the author didn’t have feelings that could ever get hurt.

But DeRuiter is a human. She’s a human who goes online, and happens to read reviews of her work published on gigantic international outlets. And Reese, who knew that she was writing for the literal New York Times, should have recognized that reality.

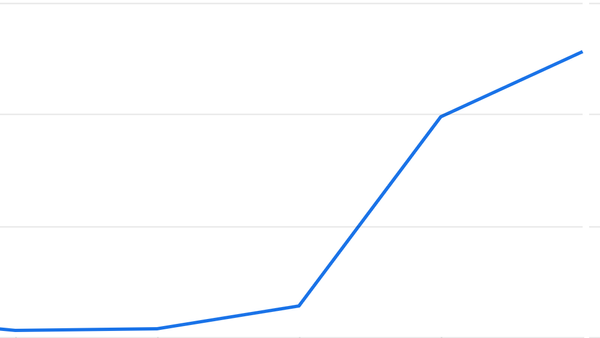

Why didn’t she? Because like so many of us, she was trained to ignore individuals and focus on numbers going up.

Under the current economic and business models of digital publishers like The New York Times, most money made through content depends on the volume of visits to a particular page of a website.

“We are fed culture like foie-gras ducks, with more regard for volume than quality—because volume, sheer time spent, is what makes money for the platform through targeted advertising.” – Kyle Chayka, “Filterworld.”

Because publishers expect their readers to always be passive “foie-gras ducks”, they get nihilistic. And when publishers start with a presumption of nihilism they pass on that nihilism to their readers. They think that their audience is disillusioned, that they’ll expect rage bait, ads, and spam. So the publishers think “let’s give them what they want”.

Except this passivity is also an escape from responsibility and any meaningful change. It’s basically giving up.

Money ISN’T in the Number of Views

Websites like The New York Times publish inflammatory pieces like Reese’s review of DeRuiter’s book because those websites are only valued in terms of their views.

Except here’s the problem: views don’t actually equal to money.

“The value of attention ‘packaged’ by online advertising is declining. Online advertising is increasingly ignored—or actively resisted—by the public at large. Second, the ‘attention’ that ads do receive is increasingly garbage–the product of a massive, fraudulent economy designed to extract money from advertisers.” – Tim Hwang, “Suprime Attention Crisis”.

I’m a professional marketer, and my entire career is built on refusing the trap of programmatic advertisers, chasing virality, and maximizing views at all cost. I’ve seen, time and time again, that the “mainstream” approach to marketing doesn’t actually work.

Too many of us assume that the only way to make money online is by maximizing traffic. That’s not true. You don’t want as many views as possible. You want the right views.

Look, not all views even convert. And not all conversions are the same. When you’re selling books the money isn’t views. It’s books sold. You don’t need to play the algorithm. And when you’re selling subscriptions to the New York Times, the money isn’t the views. The money is the amount of subscriptions sold.

But that’s not what the advertisers want the publications and creators to think. Except wait… that doesn’t help advertisers either since volume-based ads aren’t effective.

The traffic-centered business model that’s dominating the internet doesn’t work for anybody. And volume doesn’t have to be the only way to conceptualize making money online.

The internet doesn’t have to be mainstream or monolithic. Open web doesn’t mean unified web. Open web means that anyone who wants to find you can find you. Not that you should be found by as many people as possible.

Publishers like the Times treat virality like winning the internet, as if the internet is a single market to be dominated. In response, I think of a quote from The Great Gatsby:

“I like large parties. They’re so intimate. At small parties there isn’t any privacy.”

Except it seems that we keep treating the largest party in history (that is, the internet) as if it also has to be the largest concert, with all guests held captive, forced to stare at the same stage. We get upset when some of those guests decide to leave and go somewhere else. We treat the ends of our parties as tragedies, forgetting that happy guests will often want to come back, while prisoners try to escape from their prisons.

Don’t Listen to The New York Times. Buy Geraldine DeRuiter’s Book

Reese finishes her review by writing:

“While reading this book, my eyebrows were sometimes raised in admiration; too often, sadly, in exasperation.”

Unfortunately for Reese, she didn’t manage to get even a second of admiration from me or from thousands of others reading her terrible review.

I don’t know what she thought she was doing. That review felt mean, personal, and frankly immature.

I think that reviews like Reese’s miss the point of why we choose to write or read. But the opinion of critics doesn’t always matter. As Mina Le says in the video I referenced earlier:

“You don’t have to be well-liked by critics to be well-liked by the public.”

And DeRuiter is certainly liked by the public. She rose to fame thanks to her blog and her sincere, enthusiastic, infectious personality. I am honored to have had the spare cash to buy her book three times.

And I hope that you, my dear reader, will try to buy “If You Can’t Take The Heat” at least once.

Top 3 Reading Recommendations

- “If You Can't Take the Heat: Tales of Food, Feminism, and Fury” by Geraldine DeRuiter.

- “If You Can't Take the Heat: Tales of Food, Feminism, and Fury” by Geraldine DeRuiter.

- “If You Can't Take the Heat: Tales of Food, Feminism, and Fury” by Geraldine DeRuiter.

;)

Musical Minute

“Lose Control” by Teddy Swims.

I absolutely love Teddy Swims’s voice in this. I just can’t stop listening to this song. Speaking of loneliness:

“Somethings got a hold of me lately

No, I don’t know myself anymore

Feels like the walls are all closing in

And the devil’s knocking at my door

Woooahhh

Out of my mind, how many times

Did I tell you I’m no good at being alone

Yea, it’s taking a toll on me

Trying my best to keep from tearing the skin off my bones”