Soft Power

Emotions and open conversations about feelings are not only acceptable in professional settings, they are MANDATORY for creating a truly productive, effective, and equitable work environment.

Stop giving emotions a bad name in professional settings.

In the past year, I’ve had two men in my network, who I had close personal relationships with, claim that talking about feelings wasn’t “professional”.

The first time, I assumed that the problem was isolated to the man who said it. We’ve had other issues in our relationship, and I definitely carry some blame for not clearly setting expectations. So, I figured, I’d just let it go and not talk to that person much anymore.

The second time happened today. A completely different man, a different situation, a different professional dynamic, but the same response. “Be professional,” a statement made to shut down questions about how the man’s behavior made me feel.

ADMD’s tagline is “the newsletter about the emotions behind marketing work”, so as you might imagine I take emotions and their role in professional interactions very seriously.

So, let me respond to that attack on one of my core beliefs about business, work, and collaboration head on.

Because I know for a fact that one of the men I discuss reads this newsletter. So yes, I’m talking to you.

But I’m also talking to anyone reading these words:

Emotions and open conversations about feelings are not only acceptable in professional settings, they are MANDATORY for creating a truly productive, effective, and equitable work environment.

Let’s go.

Why We Care

Let’s start with the data, because I don’t want to lose all the men reading this due to assumptions that “oh, this is just one of Mariya’s fluffy feelings newsletters”.

Emotions and Gender Bias in Performance Feedback

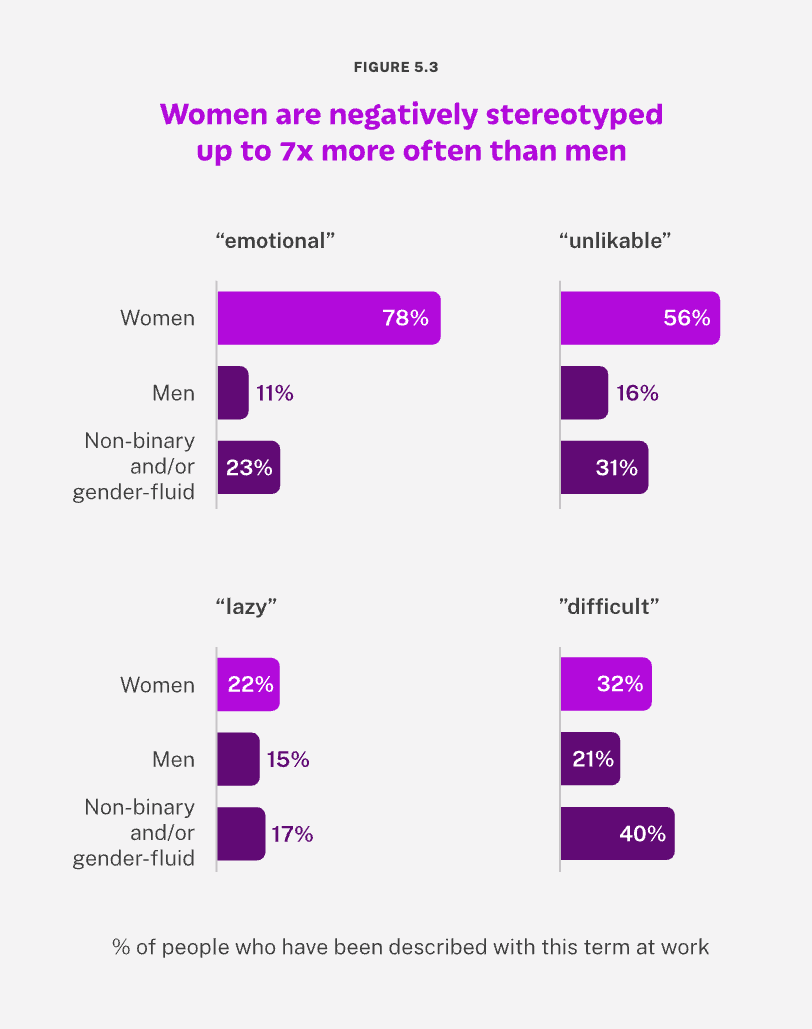

Here’s a chart from a report released this summer by Textio:

If you can set aside your own biases, consider that we’re talking about a 67% gender-based difference in how people are treated at work (or 55% if comparing with non-binary / gender-fluid individuals).

67%.

That’s the difference in how much more frequently humans who identify as women get accused of being “emotional” compared to humans who identify as men.

I don’t know about you, my readers. But I think a statistic like that is a problem worth digging into no matter what that adjective might be.

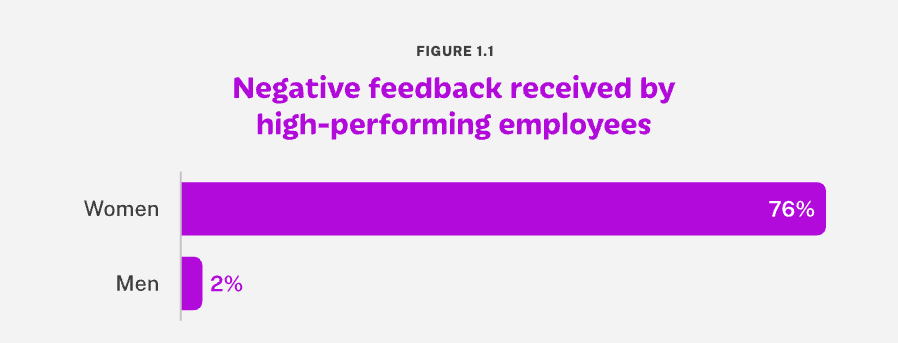

Furthermore, the amount of negative feedback in general is vastly different for women vs. men in the workplace, especially for high performers:

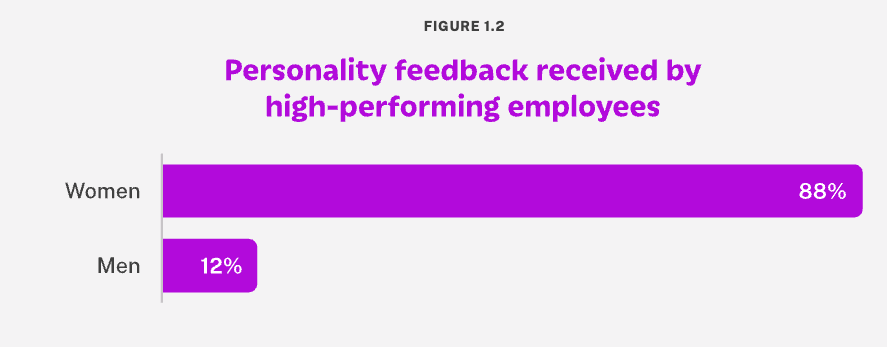

A lot of the feedback disproportionately received by women also focuses on their personality (such as all the examples shown above, with personality traits like “emotional” or “difficult”, rather than specific skill-based performance feedback):

The effect of pummeling high-performing female employees with non-actionable and negative feedback is (as you might guess) pretty detrimental to their workplace morale:

Textio’s report gives us two conclusions:

- Women get criticized for their personality in unhelpful ways in the workplace a lot more often than men or non-binary individuals.

- People who get unhelpful feedback aren’t happy in their places of work.

Okay, that’s the basics covered.

Still with me? Good.

How Allowing Emotions Into Work Improves Outcomes

Now, let’s talk about the impact that accepting emotions at work can actually have on the things that businesses supposedly care about, like productivity, effectiveness, and collaboration.

Some fun facts about emotions at work:

- People are more innovative at work when experiencing positive feelings.

- When employees minimize the experience of their negative emotions, they behave in more unethical ways, leading to lower profitability and higher turnover for their organizations.

- Emotions act as a proxy for workplace productivity and including emotional feedback in work meetings make employees more effective.

- Employees who are more conscious of their emotions and able to regulate them have better relationships with peers and their teams tend to perform better overall.

TLDR: explicitly incorporating emotions into workplace conversations, professional skill development, and organizational priorities makes those organizations more successful.

The data is clear. If you are a leader and care about your team and business doing well, then by calling emotions “unprofessional” you’re shooting your organization in the foot.

Let’s all be mature here and actually confront our feelings about feelings. (I believe that all of you reading these words are more than capable of it.)

Ways Emotions Show Up at Work

Okay, so what does it actually mean to be “emotional” in professional settings?

We’ve got a couple layers to uncover, so bear with me.

Levels of Emotions in Organizations

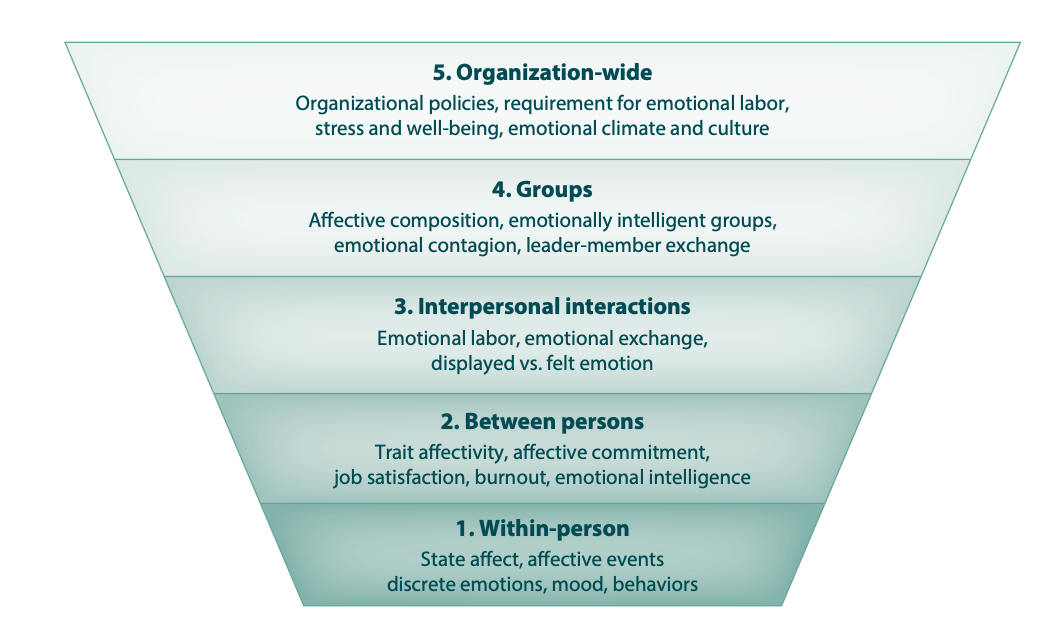

As with most topics, when we discuss a concept within work we need to address the different levels that show up in organizations. One way of breaking them down is into the following five levels:

- Organization-wide policies and culture

- Group emotional exchanges

- Interpersonal interactions

- Interpersonal dynamics

- Individual traits and moods.

This means that as we talk about emotions and handling them in professional settings, we need to cover every layer of how they manifest, from the large-scale organizational perspective to internal beliefs and personality traits of individual professionals.

In this piece, I’m mostly focused on the bottom 3 layers: interpersonal interactions, interpersonal dynamics, and individual traits / moods. In other words, we’re talking about how emotions affect how we communicate with people at work and how we think about those emotions in our own heads.

When someone is accused of being “emotional”, that label assigns an individual personality trait to someone else based on their interactions with other people, including the one making that accusation.

For example, if I am talking to a man named Dave, and he calls me emotional, Dave is labeling my personality based on how he perceived our communication with each other. His perception is then likely to color any of Dave’s future interactions with me, spilling over to our entire professional relationship and capacity to collaborate on projects or tasks.

Social Power

Here’s the thing: we often deny emotions the power that they could help us yield.

I am using the definition of “social power” as described in the book “The Power Code” by Katty Kay and Claire Shipman:

“the ability to exercise one’s will, to influence others, to effect change.”

Basically, power to actually get things done in ways that we tend to care about in professional settings. Power helps us reach our targets, complete our to-do lists, and enable others to do the same.

So, if “getting things done” power requires us to successfully influence others at work, then we need to understand and yield all levers of influence, including… emotions.

Like it or not - people are emotional creatures. We feel things, all the time. And if our actions are at least in part motivated by how we feel, then to truly influence others we need to be able to impact feelings.

Otherwise we’re simply leaving our own and our colleagues’ potential in the sad dumpster labeled “supposedly professional conduct” by some white dudes in the 50s who were too tired of hearing about feelings and banned them from the office.

Getting Things Done with Others

One of the reasons why being “emotional” is seen as a flaw is because stopping to think about emotions is getting in the way of simply pushing through and focusing on the task at hand.

The common wisdom is - if we’re talking about doing things, we’re not getting anything done, so the talking is a waste of time.

Let me propose a different perspective. Have you ever heard of David Allen?

You might know him as the author of the iconic business book “Getting Things Done” or the GTD method. It’s kind of the cornerstone of most modern productivity advice, and one of the most followed workplace effectiveness frameworks in the world.

Allen also co-authored a new book this year, called “Team: Getting Things Done with Others”. And I would trust him as an authority on those kinds of topics. So, isn’t it interesting that in that book Allen and his co-author wrote:

“There was a time when discipline and willpower were seen as the keys to making the consistent behavioral changes that would lead to great performance. Implicit in that belief was the idea that success was linked to inner strength—individuals’ ability to get themselves to do things they didn’t really want to do. And if they simply huffed enough willpower, and puffed enough discipline, any doors blocking the attainment of superior performance would eventually blow right over.

In recent years much of the research into change has pointed in a different direction. If you want to change your behavior—and performance—you’ll want to pay less attention to your willpower, and much more attention to what your environment allows or encourages you to do consistently.”

Emotions can only be seen as a distraction when we perceive them as separate from the actual work we’re supposed to do. But when our entire environment is what actually determines the level of our productivity, time spent around the work is just as important for getting things done.

Emotions are Core to Professional Performance

Emotions are not a hindrance to workplace performance. Instead, emotions are a core aspect to improving productivity both for ourselves and others in our professional lives.

Simply pushing through our feelings will not make us better at our jobs.

Ignoring feelings won’t make us better at our jobs.

Ignoring the feelings of others won’t make them better at working with us.

And attacking others who we work with for being too emotional, feeling the wrong things, feeling too much, or gasp TALKING ABOUT FEELINGS is – unproductive, detrimental to workplace outcomes, and perpetuating harmful gender stereotypes that have no place in modern workplaces.

Making Emotions Professional

What would a better and more emotionally conscious path forward look like in professional environments?

I think it requires a couple of elements:

- Establishing an expectation of institutional courage

- Creating shared pools of meaning

- Turning personal emotions into professional strengths.

1 - Establishing an Expectation of Institutional Courage

In her recent book “Radical Respect”, Kim Scott talks about two kinds of organizational cultures:

- Institutional courage: “leadership commitment to seek the truth and to take action on behalf of those who trust or depend on the institution—even if it’s unpleasant, difficult, and costly.”

- Institutional betrayal: “when an institution mistreats those who trust or depend on it”, with examples like “victim blaming, sweeping incidents under the rug, and the like”.”

Ignoring emotions and telling individuals who bring up emotional impact on their work and in their professional relationships is institutional betrayal.

And as Scott writes, that’s a big problem:

“Institutional betrayal is often cheaper in the short run but devastatingly expensive or even deadly to the institution in the long run.”

When a young woman you work with comes with a complaint about how your actions made her feel upset, it’s easy to dismiss her. Those emotional problems feel nebulous and like an issue that she should work out in her own time, off the clock.

But even if calling her “emotional” and threatening her into silence might make it easier for you to sleep tonight, you’ve just damaged the trust in your relationship, made the work environment hostile and incompatible with authenticity, and harmed that woman’s ability to get her work done in a productive way.

In what world is that making you more “professional” or better at business?

If you want to improve your professional outcomes or be a better leader, then strive for institutional courage.

2 - Creating Shared Pools of Meaning

One of my favorite books, “Crucial Conversations”, includes the concept of a “shared pool of meaning”.

A shared pool of meaning is basically all of the information that is openly introduced into the context of a conversation. It’s all the facts, statements, and data points that were shared by all participants in that particular discussion.

So if you and I are talking, and you say “We need to increase our website traffic by 10% this quarter” and I reply “I feel scared that the goal is unrealistic” then our shared pool of meaning looks like this:

- We have a goal of increasing website traffic by 10%

- We need to achieve that goal this quarter

- We aren’t sure if the goal is realistic

- At least one person feels negative emotions (fear) about this goal.

If you look at that list, you can see that the emotion serves as a barrier to achieving the pragmatic objective.

It’s easy to blame me for introducing that barrier, because if I wasn’t scared then we could just get straight into how we can achieve that target.

However, if I didn’t share that fact, I would have still felt the same way. And if my fear wasn’t introduced into the pool of meaning, it would have never been acknowledged and it could have never been discussed. We can’t solve problems if we don’t talk about them.

So, introduce feelings into shared pools of meaning.

3 - Turning Personal Emotions Into Professional Strengths

One of the best books I picked up recently is called “Trust Yourself: Stop Overthinking and Channel Your Emotions for Success at Work”. Here’s one particularly relevant section:

“Emotions are a source of sensory intelligence and insight that give you important information about your needs or actions you can take to respond more authentically. Even so-called bad or negative emotions have a function. For instance, fear is one way to keep yourself safe and protected, and guilt signals the need to make amends. When you start thinking of your emotions as messengers, your relationship to them changes.”

You don’t have to view emotions as an inconvenience or a barrier to professional success.

Instead, acknowledge emotions as another powerful data source within your own work and your organization at large. If you pride yourself on making data-driven decisions, then you need to incorporate the insights provided to you by millions of years of evolution that made human brains into the miracles that they are.

A Note of Hope

I really hope that I might have changed some minds today, or at least opened up your eyes to other ways of thinking about emotions and professionalism.

And if you’re one of the people I mentioned in the introduction, thank you for reading this far. I suspect it wasn’t easy, and I applaud your bravery in pushing through.

Please know, I forgive you. Just let me have the space to feel things in our work together – my emotions are one of my greatest strengths. You wouldn’t have respected my work so much if I didn’t channel my feelings into it as openly as I do.